Summer Love. A photography project on the 2023 Cutro shipwreck

Abstract: On the morning of 26 February 2023, a shipwreck occurred off the coast of Steccato, in Cutro, in the province of Crotone (Calabria, Italy). The boat was carrying about 180 migrants from countries including Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Somalia and Palestine (Mallamaci, 2024).

Human traffickers, especially Turkish and Syrian, gathered all migrants in Istanbul. Once they arrived in Çeşme, on the Aegean Sea, they were put on a boat which collapsed immediately. At that point, they boarded the Summer Love, a 25-metres long Turkish gulet — a fishing vessel, often used for short-distance tourist cruises — flying the Greek flag.

94 lifeless bodies were found.

35 of them were children.

Keywords: shipwreck, Cutro, migrants, Turkish route.

***

Vincenzo Luciani was asleep when he got a phone call in the middle of the night. “Vincé, get down here,” his friend pleaded at the other end of the line. “I can hear people screaming but I don’t know what’s going on.” He got dressed in a rush and drove his rusting white Nissan 4x4 down the road to the nearby beach of Steccato.

Vincenzo, 50, runs a small fishing business specialising in cuttlefish. He has the tanned skin of someone who spends a lot of time at sea, and ripples of thin grey hair held back with gel frame the furrows in his forehead, undulating like the sea floor. White stubble peppers his grief-stricken face as he talks to the camera. “When I got here, I was terrified by what I saw, but I didn’t have time to think,” Vincenzo recalls, tears welling up in his eyes. Behind him, the waters of the Ionian sea fade from green to grey, white froth lapping on the thick beige sand at his feet. Sunbeams shine through the gaps in the dark clouds, crossing the hazy sky in the distance. Beyond the pine grove delimiting the beach, the built up area of Steccato di Cutro — a series of almost identical one and two-story houses, some left unfinished, surrounded by fruit trees, stocky palms and cactuses growing out of fences — interrupts the succession of yellowing fields along the SS106, the coastal road connecting Catanzaro and Crotone.

“I jumped into the water to catch the people in the sea,” Vincenzo explains, running his hand over his face, shaking his head slowly in disbelief. “I thought they would be alive, but they were all dead.”

***

On the early morning of 26 February 2023, a wooden sailboat carrying around 180 people — the exact number remains unknown — crashed into a rock, metres away from the shore of Steccato. Off the eastern coast of Calabria, a south-easterly gale heaped up the waters of the Ionian sea, waves rose up to four metres high. The gulet — a wooden sailboat normally used for short-distance tourist cruises in the south-western Aegean — had left five days earlier from Turkey; it was spotted the night before the shipwreck by European border authorities as it rocked in the rough waters around 40 kilometres from dry land. With the storm not yet in full force, it was deemed suspect, but not at risk (an investigation is underway to shed light on the communication failure between Frontex, whose planes sighted and reported the boat to the local authorities, and the Italian coastal guard, who failed to intervene to prevent the tragedy). X-ray footage of the boat shows a person exiting the cockpit and moving towards the bow. Crammed tight below deck, invisible to surveillance cameras, were migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia, Syria, Iraq. They’d been instructed not to move so as to avoid capsizing the vessel, stretched far beyond capacity. Their phones were off to avoid any signal being intercepted. They were close, they’d been informed.

Upon impact with the rocks, the Summer Love smashed apart, thrusting its disoriented passengers into the choppy, freezing waters. Many of them drowned before they could reach the shore, one hundred metres away.

***

It wasn’t until the sun rose that Vincenzo realised the scale of the devastation. Tens of lifeless bodies strewn across the beach all around him. As more and more people in the throes of the waves appeared in the headlights of his jeep, he reached to grab and pull them out, but the undertow kept dragging them back. “It was an inhuman effort,” Vincenzo says, eyes to the ground.

“The boat was shattered, it looked like it had been put through a washing machine. Pieces of it scattered everywhere,” he turns to look across the beach, frowning. “Wrecked.”

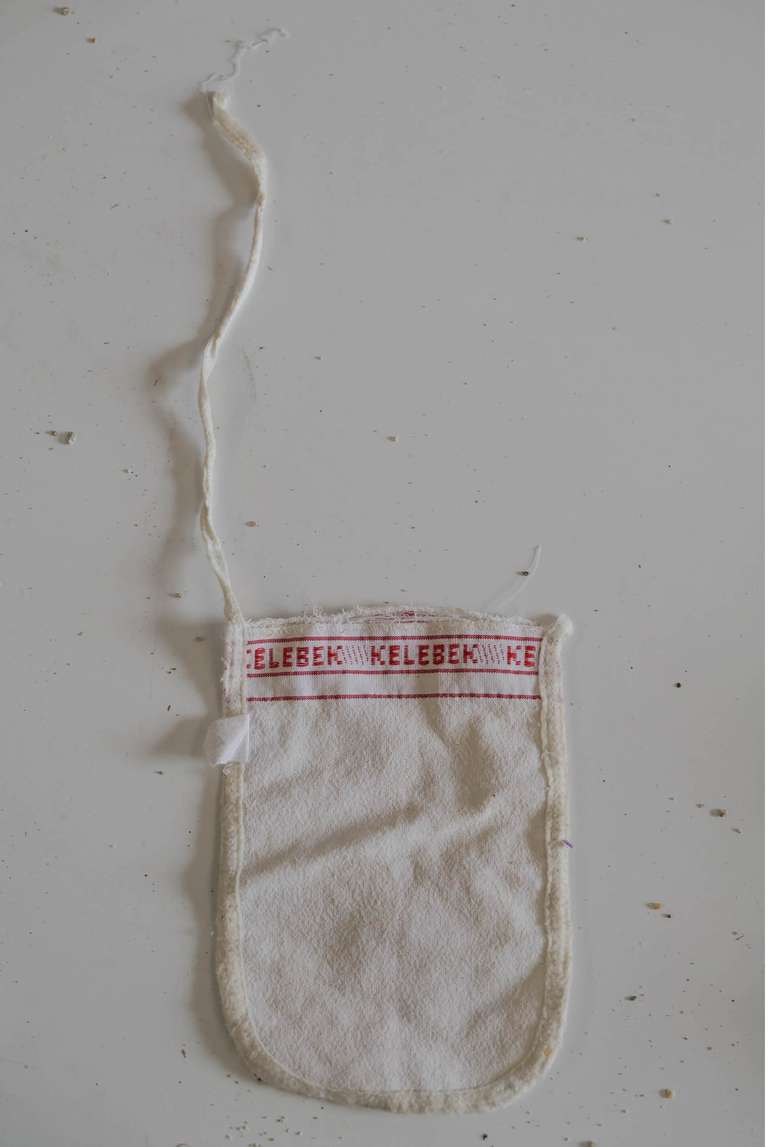

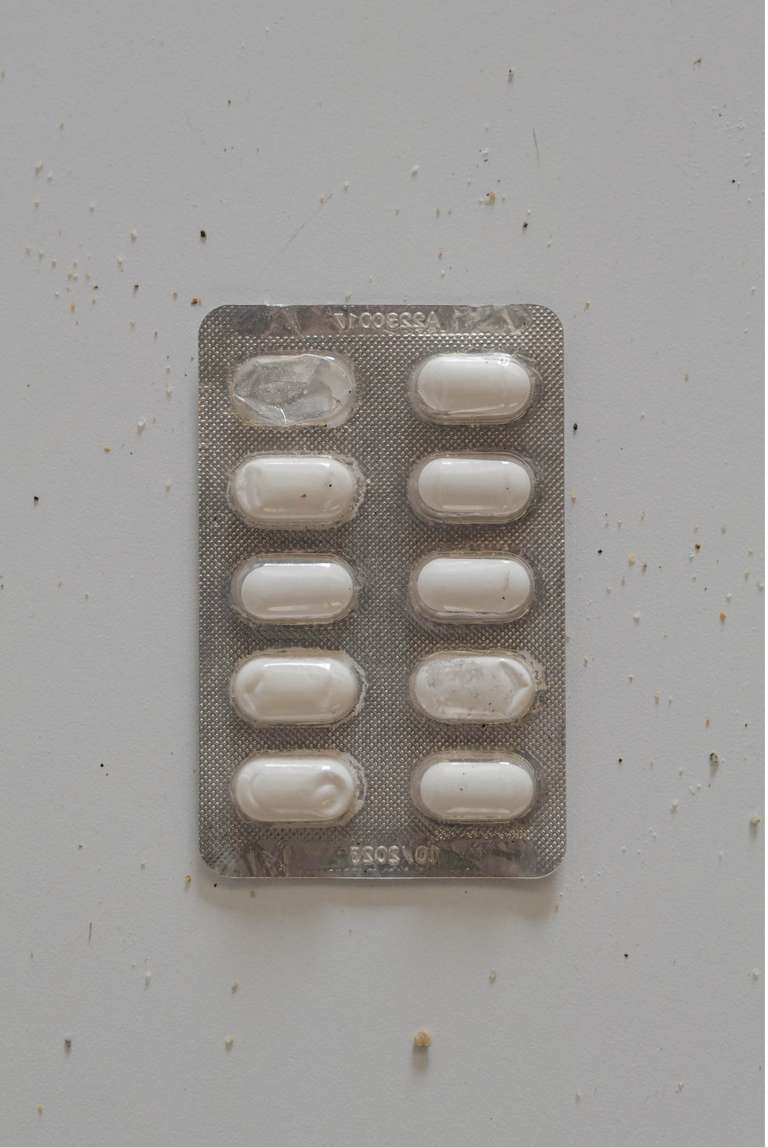

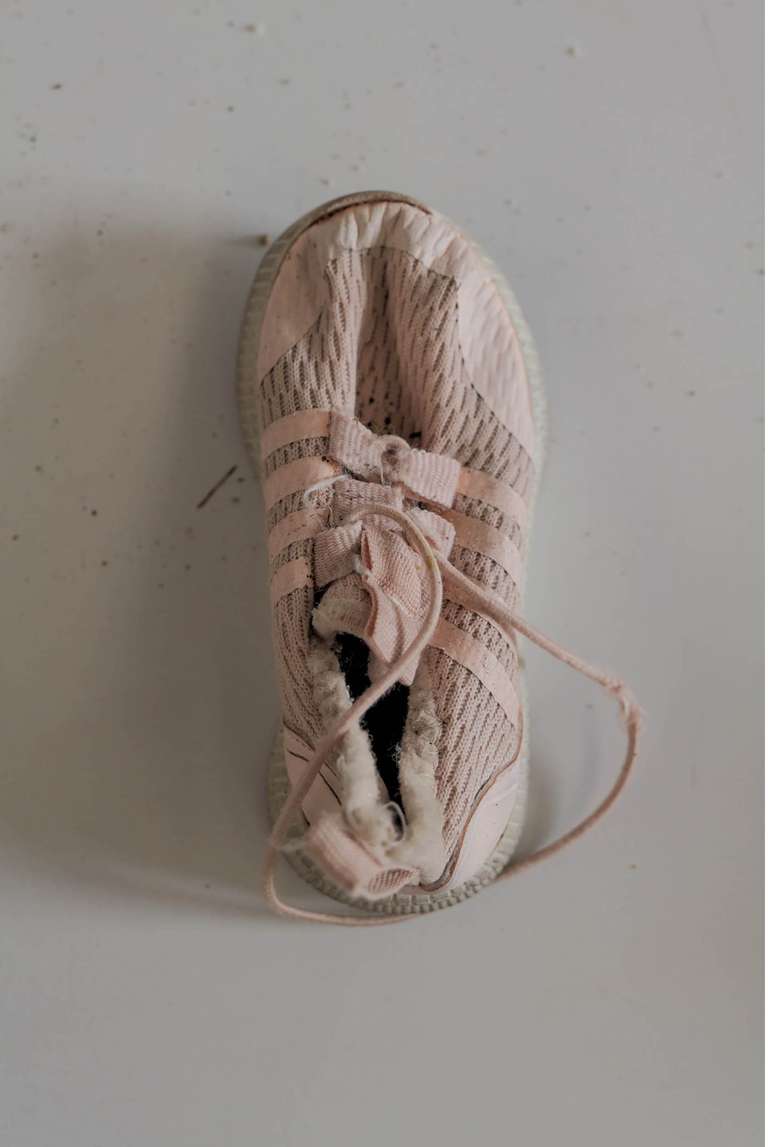

Ninety-five people, including thirty-five children died in the shipwreck off the coast of Steccato. Eighty survived, and an unknown number remain missing. For days, Vincenzo kept patrolling the beach and surroundings, looking for them. The sea, gradually growing calmer, threw up shoes, clothes, rucksacks, food wrappers with nutrition facts in faraway languages. Flowers were planted into the sand, and out of pieces of wood from the shattered boat, makeshift crosses were fashioned in memory of those who lost their lives. “The beach is like a cemetery,” said a local woman to a journalist, looking out to the sea. “It’s beautiful, but deceptive.”

***

On 9 March, the Italian council of ministers held an emergency meeting in the golden ochre-painted town hall of Cutro, a village set back in the hills above the Ionian coastline. “Shame on you! Assassins!” chanted protesters lining the street, throwing stuffed toys at the government cars driving along the main street. “They could have been saved!”

“We are determined to defeat human trafficking, which is responsible for this tragedy,” prime minister Giorgia Meloni announced at the press conference following the meeting. “Our response to what happened is a policy of greater firmness”. Down by the beach, bodies kept washing up on the shoreline among the wrecks of the wooden boat.

The Cutro decree, approved in May 2023, steps up punishment of human smugglers, increasing the maximum prison term from five years to thirty. The measure is meant to dissuade people from joining human smuggling operations. What it fails to take into account is that smugglers themselves rarely partake in the crossings. The criminal groups who organise the journeys are usually based in the countries of departure, where the Italian authorities have no jurisdiction. The boat drivers (scafisti) who end up being singled out and punished as smugglers are often asylum seekers or migrants who have found themselves steering the boat by happenstance or coercion.

According to the report “From Sea to Prison — The Criminalisation of Boat Drivers in Italy”, “the people who drive the boats do so for a vast range of reasons.” These include coercion or monetary incentives by the trip organisers. Boat drivers “essentially represent the last links in a much greater chain, the most important parts of which remain in the shadows.” Far from being responsible for deaths at sea, “the people who drive boats are often themselves migrants who have been blocked from entrance into Europe and who risk their own lives to cross the border.” The persecutions meant to break the business model of people smugglers often end up criminalising vulnerable people who are seeking safety and opportunity.

The Cutro decree also makes it more difficult for illegal migrants to stay in the country, by limiting the granting of special protection status and doing away with basic integration services.

First introduced in 2018, special protection could be applied to people who did not qualify for asylum or refugee status, yet risked being persecuted in their country of origin, were fleeing war and natural disasters, as well as those with family or social and economic ties—such as a job—in Italy. People offered special protection status could live in Italy for two years, renew their residence permit and convert into a working permit.

Following the amendment, only migrants whose fundamental rights might be violated if they were to return to their country of origin can be granted special protection status. Those fleeing war and natural disasters or those with family ties or a demonstrable level of social integration in Italy, do not qualify on those grounds alone. Whilst grantees of special protection status will be entitled to work, they will no longer be able to convert their residence permit into a work permit at the end of the two-year period.

Psychological support, legal aid and language courses will no longer be guaranteed in migrant reception centres.

***

The crosses on the beach of Steccato have been replaced with colourful parasols, the flaps of their fabric coverings fluttering in the evening August breeze. A disorderly arrangement of whites and greens, reds and yellows and stripes forming an uncertain barrier against the implacable sea.

To the north, the coastline curves into the promontory of Isola Capo Rizzuto, shrub-covered white clay rock descending into the turquoise water. On the opposite end of the beach, a sculpture-like pile of driftwood, forming a crooked cross is one of the few signs of the tragedy that unfolded here six months ago.

“It’s not easy to forget,” says Vincenzo. “I try to fall asleep, but I wake up immediately. I see the images of those people drowning. I won’t be going into the sea for some time.” Since the shipwreck, Vincenzo has been helping his mother in her nearby hotel.

In the back of his rusty white 4x4, he keeps pieces of the shattered boat, spelling out the letters of its name: Summer Love.

***

Sitography

Consiglio dei ministri n. 24, 9 marzo 2023, www.governo.it/it/articolo/consiglio-dei-ministri-n-24/22009.

Fasano G., Naufragio Cutro, le ultime immagini del barcone: il video di Frontex che ora è in mano alla Procura, in “Corriere TV”, 22 marzo 2023, video.corriere.it/cronaca/ultime-immagini-barcone-cutro-video-frontex-che-ora-mano-procura/6c83ccec-c8c1-11ed-85b6-6207f76c958d.

From Sea to Prison. The Criminalization of Boat Drivers in Italy. A report by ARCI Porco Rosso and Alarm Phone with the collaboration of Borderline Sicilia and borderline-europe, 15 October 2021, www.borderline-europe.de/sites/default/files/background/from-sea-to-prison_arci-porco-rosso-and-alarm-phone_october-2021.pdf.

Giuffrida A., “The beach is like a cemetery”: Italian village grapples with shipwreck aftermath, in “The Guardian”, 27 February 2023, www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/27/italy-shipwreck-calabria-migration.

La protesta a Cutro, lanciati peluche contro le auto dei ministri, in “quicosenza.it”, 9 marzo 2023, youtu.be/ZZhiYT9mWro?si=EyAfDaWovQQzntPt.

Legge 5 maggio 2023, n. 50, Disposizioni urgenti in materia di flussi di ingresso legale dei lavoratori stranieri e di prevenzione e contrasto all'immigrazione irregolare, www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2023/05/05/23A02665/sg.

Mallamaci A., Summer Love. With an interview to Motjaba Rezapourmoghaddam, 15 June 2024, youtu.be/PUwpeAyX1rA.

Naufragio di Cutro, la testimonianza del pescatore-soccorritore Vincenzo, in “Vatican News. Italiano”, 4 marzo 2023, youtu.be/Yeoh1WTYr6Q?si=dN06PPIQG5fczS8l.

Zanuttini, P., Ritorno a Cutro dopo il naufragio, in “Il Venerdì di Repubblica”, 8 agosto 2023, www.repubblica.it/venerdi/2023/08/08/news/cutro_steccato_naufragio_migranti_morti-410420482/.

The authors

Alessandro Mallamaci, until 2008, worked as an educator, collaborating with esteemed brands like Leica. He had the privilege of lecturing at Columbia College in Chicago, USA, and currently teaches at the Academy of Fine Arts in Perugia. His artistic projects and books have received awards and have been featured in exhibitions across many countries in Asia, USA and Europe. Teresa O’Connell is a writer and editor who grew up in Cosenza, Calabria and lives in Berlin. She has collaborated with media and publishers across Europe. Her narrative non-fiction explores the intersection between personal stories and global issues.