Bodies, Memory, Territories. A Testimonial Theatre Experience with Colombian Afro-Descendant Women

A. Miramonti, Bodies, Memory, Territories. A Testimonial Theatre Experience with Colombian Afro-Descendant Women, in “Educazione Aperta” (www.educazioneaperta.it), n. 9 / 2021.

PDF: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.5163990

The context: the Colombian armed conflict and the project “Mingar la paz”

The Colombian armed conflict is a low-intensity war that began in the mid-1960s, involving the Colombian state and several armed groups (guerrillas, paramilitaries, drug traffickers and other unidentified groups) and continues to date. The conflict resulted in more than 250,000 victims, 81% of whom were civilians and forced over 7 million people to leave their homes, making Colombia the second country in the world for internally displaced population, after Syria. One in three of the 7.6 million officially registered victims of the conflict are children and it is estimated that 45,000 minors were killed during the conflict. In November 2016, after four years of negotiations conducted in Havana with the mediation of the Cuban government, the Colombian government and the country’s largest armed group, the FARC-EP (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - Ejército Popular), signed a historic peace agreement that led over 8,000 FARC-EP fighters to hand over their weapons to the United Nations and return to civilian life in 2017 (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica 2017). Furthermore, from 2001 to 2019, over 60,000 fighters from different armed groups left their weapons individually and returned to civilian life (Agencia de Reincorporación y Normalización 2019a). One of the areas most affected by the conflict are the territories of the afro descendant communities of the Colombian Pacific Coast. These areas have been affected by guerrillas, paramilitaries, narcotrafficants and the Colombian army due to the natural resources of this region and its strategic position on the Ocean. In spite of having been affected by decades of violence, Afro-descendant communities in the region have managed to develop resistance strategies and managed to effectively coordinate with local governments and international actors to protect their territory from the infiltration of armed groups. The project “Mingar la Paz: Teachings of Yurumanguí to Think of Territorial Reparation and Peace Building in the Colombian Pacific” is an initiative of the Faculty of Law and Political and Social Sciences of the National University of Colombia in Bogotá that started in 2017 with funding of this same university. The project’s multidisciplinary team includes researchers from the National University and the afro descendant communities represented in the Yurumanguí River Community Council (hereinafter simply called “the River”) in the rural area of Buenaventura. The overall objective of the project is to consolidate a network of action-research on the relationship of these communities with their shred memories and territories, and to offer opportunities for collective reparation from the past and present wounds of the ongoing armed conflict. The Project seeks to strengthen the peace-building process of the afro Colombian communities of the Pacific coast and to investigate how the world views of afro descendant communities (that poses a close relationship between their life and their territory) can be articulated with the reparation policies designed by the Colombian Government.

In particular, the project aims to contribute to three axes related to the integration of the representations of the territory of the afro descendant communities with collective reparation processes.

Narrate the conflict to build peace. This axis consists of an exercise in reflection and reconstruction of the community’s narratives on the social and territorial effects of the armed conflict. This reflection is taken as a political resource to empower the communities to protect their territory from external aggressions and also and a symbolic vehicle to recover and value different ways of accounting for the violent past, anchoring them in the present, to contribute to collective reparation.

Yurumanguí, territory of peace and dignity. This axis seeks to advance a proposal for “territorial reparation” that contributes to the restoration of the victims’ dignity, in accordance with their constructions of identities, their forms of government and the ways they care of their territory.

Afro descendent dignity, elements to think about peace. This axis is aimed at understanding the relationship between the forms of social organization that arose around artisanal mining and other traditional economic activities on one hand and the forms of territorial reparation for the afro descendant communities of the Yurumanguí river basin on the other hand. While this article leaves the in-depth analysis analyse of the specific resistance strategies developed by these communities and intentionally focuses on the analysis of a specific drama-based case study, it is worth noting that this intervention was proposed by the communities as a contribution to their ongoing efforts of the communities. Moreover, the project considers that the generation of knowledge about peace initiatives carried out by the afro descendant communities of the Colombian Pacific coast is needed, as it allows generating contributions for the construction of peace from the local culture. Starting from making visible the practices of peace of these communities, the project seeks the construction of a space for interaction between academia and society, which serves as the basis for the consolidation of a network of thought for peace, that recognizes the processes organizational structures and, based on the knowledge generated by the project, propose alternatives for territorial reparation.

At the beginning of 2018, the research team contacted the representatives of the Black Communities Process in Buenaventura and obtained the authorisation to travel to the River, meet the elected representatives of the communities and presented their research objectives. The researchers obtained to hold meetings in the communities, where they presented the objectives of the research and received the feedback of the communities. After these consultations, the communities of the Yurumanguí River agreed to participate in the project.

The partnership with the “Arts for Reconciliation” project

In April 2019, two researchers of the “Mingar la Paz” Project who are also part of the “Guía Nómada” collective of former students of the National University in Bogotá contacted the “Arts for Reconciliation” research project of the Departmental Institute of Fine Arts of Cali (hereinafter simply called “AfR Project”), and invited members of the AfR Project to organize a testimonial theatre workshop for a group of Afro-descendant women from the Yurumanguí River. The workshop became part of the activities of the “Mingar la paz” project aimed at strengthening the community resilience and collective resistance to violence through the valorisation of the afro-descendant culture and collective memory of the people living in the Yurumanguí River.

The AfR Project agreed to design and deliver the workshop as part of its ongoing research on creative techniques to accompany reconciliation processes with populations affected by conflicts. The theoretical assumptions of the AfR Project are presented in detail in Miramonti. The research presented in this article is part of the ongoing “Arts for Reconciliation” research project and aims to present the methodology and results of the workshop, as well as to formulate some reflections on the use of testimonial theatre to foster collective memory and support reparation processes with communities affected by armed conflicts.

After consultations with the Guía Nómada members, the AfR Project proposed to deliver a workshop inspired by a specific form of testimonial performance: Theatre of Witness, that we briefly introduce in the next paragraph.

The origins of Theatre of Witness

Theatre of Witness is a theatrical process systematized by the American director and playwright Teya Sepinuck over the last thirty years in the United States, Northern Ireland and Poland. The objective of Theatre of the Witness is to make visible the stories of wounds and the healing paths of people who have lived through situations of violence, conflicts and forced displacement that radically transformed their lives.

This technique aims to give the voice back to the protagonists of these events and inspire the audience with personal testimonies of resilience, courage and reconciliation. Sepinuck and his disciples have been working with this technique with ex-combatants, relatives of murdered people, abused minors, refugees, torture survivors, prisoners in life imprisonment and relatives of patients with chronic diseases. One aspect that distinguishes Theatre of the Witness from other testimonial theatre forms is that in Theatre of Witness it is always the person who lived the experience who performs her/his own autobiographical story on stage. For this reason, Theatre of Witness almost always works with non-professional actors and the distance between the actor and her character is very small. By participating in a Theatre of Witness performance, the audience can recognize in the actress or actor on stage the witness of a story that deeply marked their life. Furthermore, Sepinuck emphasizes that a Theatre of Witness play does not focus unilaterally on stories of pain. The staging is not an “aestheticization” of the suffering of the victims, with the aim of provoking a reaction of indignation in the spectator, rather, Theatre of Witness focuses on stories of wounds, healing, and transformation, and does not unilaterally focus on the witness’s past, but also on her present, talents, and dreams for the future. The entire creation process puts the witness, her story, her ancestral memories, her interiority and her projection into the future at the centre of the play. Although many works constitute a strong call for the transformation of situations of injustice and discrimination, Theatre of Witness does not primarily seek to arouse outrage in the public, but mainly to inspire them with stories of resilience and resistance, documenting, without any fiction or exaggeration, true stories of violation, struggle and reconciliation, told and performed by the same people who lived them first-hand.

At the beginning of the process, the facilitator of a Theatre of Witness process selects a group of people who have participated directly in the same historical event (for example: an armed conflict) or who share the same experience (for example: being people in life imprisonment, being relatives of people with dementia, etc.). Once the candidates have been identified, the facilitator invites them to share their stories during individual interviews. On the basis of these preliminary meetings, the facilitator identifies a group of four to eight people who she considers ready and interested to share their stories through theatre and invites them to participate in a creation workshop. The facilitator leads the creative workshop with the witnesses, and, based on the stories of each one of them, prepares the script of the work and its acting annotations, in a constant process of listening and writing, weaving the stories and points of view of each witness. The process culminates with the presentation of a play performed by the witnesses, before an audience that in many cases shares similar experiences (relatives of chronic patients, ex-combatants, etc.). These plays create spaces for empathy and reflection, and invite the audience to move from deeply rooted ideological positions to mutual understanding and reconciliation.

Testimonial theatre about the armed conflict in Colombia

Colombia has a long history of testimonial theatre, which involves actors in the armed conflict at different levels, including women and Afro-descendant communities. Just to cite a few recent examples, we can recall the work “Victus” by Alejandra Borrero (2016), where former guerrillas, former paramilitaries, victims and former members of the army intertwine their stories. Another example of theatre based on the testimonies of victims of the conflict is the play “Donde se descomponen las colas de los burros” (“Where the donkeys’ tails are decomposed”) by Carolina Vivas, based on testimonies from relatives of “false positives” (civilians assassinated by the army and presented as guerrilla fighters) in the early 2000s. There is also the autobiographical monologue “Nightwind”, by Héctor Aristizabal (2009) from Medellin, which recounts the experience of the author, a victim of torture in 1982, and of his brother who was kidnapped and murdered by an armed group in the late 1990s. We also recall the play by Carlos Satizábal “Antígonas Tribunal de Mujeres”, created with women victims of four different violations: some mothers from Soacha whose children were victims of extrajudicial executions, women survivors of political assassinations, women victims of the persecution of human rights leaders and women student leaders who are victims of judicial setups and unjust imprisonment. In this play, the victims, together with some actresses and dancers, perform on stage and present their stories. Two last examples that we remember are the plays “Perdón y Olvido” and “El Solar”, staged by the Teatro la Máscara in Cali, where Afro-descendant women who were victims of displacement from the Pacific coast act out their autobiographical stories.

The collaboration of the “Arts for Reconciliation” Project with the “Mingar la paz” Project in Cali represents the first experience of Theatre of Witness with Afro-descendant communities in Latin America. The importance of this pilot is also in bringing together Sepinuck’s experiences with victims of the armed conflict in Northern Ireland and the numerous and multiform Colombian experiences of testimonial theatre that we presented above.

The Methods

The recent epistemological debate on qualitative research stressed the need to complement research methods that elicit and analyse discursive productions of key informants (such as semi-structured interviews, questionnaires and focus groups) with body-based and art-based methods to explore embodied imaginaries, representations of the self and the other, the negotiation of shared identities and the perceived belonging to a given community. Based on these assumptions, the AfR Project decided to pilot a theatre-based workshop to investigate the links between bodies, shared memories and territories of the River. This research adopted drama-based methods inspired by Collective Dramaturgy to elicit and analyse embodied memories and autobiographical narratives of a group of afro-descendant women. The informants were involved in actively constructing the data and analysing them through their body, words and after-action discursive reflections. This case study was inspired by the field experiment methodology, where the relationship between bodies, memories and territories in a sample group of afro descendant women was not studied with covered or uncovered participatory observation, but by explicit elicitation of embodied narratives and perceptions that were performed and discussed within the group.

Both the conceptual and methodological findings presented in this paper aim at equipping future psycho-social work practitioners with tools to broaden their understanding of the link between individual bodies, collective memories and shared territories, not only analysing aesthetic processes of co-creation of identities, but also actively accompanying them.

This research can be methodologically defined a participatory action-research, as defined by McIntyre and a qualitative case study as defined in Creswell and Poth. The empirical evidence is composed of field notes, photos and videos taken by the author and based on his participatory observation of the workshop from the specific point of view of the facilitator who designed, facilitated and co-evaluated the workshop and directed the staging of the play. The oral comments of the participants were noted, but not recorded.

The empirical evidence was analysed in light of the research question and some key themes emerged during the workshop were identified. The remaining part of this article presents the steps of this creative process and the key findings.

The preparation of the workshop

The objectives that the Guía Nómada group and the Arts for Reconciliation Project agreed for the workshop were:

Offer a creative workshop where a group of women from the river could share their autobiographical stories and investigate through art the relationship between bodies, memory and territories of the River;

Provide a space for healing and symbolic reparation to the inhabitants of the River, who over the last decades have been affected by the violence of the armed conflict;

To creatively investigate how the social transformations under way in the Afro-descendant communities of the Colombian Pacific are expressed through music and song.

The workshop was initially aimed at the six women from the River as participants. Subsequently, the organizing team considered it appropriate to add to the participants a social leader from Buenaventura, for her work in promoting the memory of afro descendant communities in the Pacific, and a graphic design professor from the institute of Fine Arts in Cali, for her experience of artistic work with Afro-descendant groups in Buenaventura. In addition, the three people from the Guía Nómada organizing team decided to actively participate in the workshop and take on the role of participants. The unifying element of the experience of all the participants was having been in contact, in different ways, with the territory of the River and its culture. Consequently, the participants were:

Six Afro-descendant women from the Yurumanguí River, selected for having been active in promoting historical memory and the peaceful coexistence in the paths of the River. Among them it is important to highlight an arts teacher from a secondary school in the River and a fifteen-year-old student from the same school;

A social leader from Buenaventura, with a long militancy in the Black Communities Process (Proceso de Comunidades Negras);

Three members of the Guía Nómada collective, who coordinated the workshop (two women and one man);

A professor at the Departmental Institute of Fine Arts in Cali, with a long experience working with Afro-descendant communities in Buenaventura.

The author of this article designed the workshop in close collaboration with the Guía Nómada participants, facilitated it and collected written notes, photos and videos on the workshop and the final play.

This composition of the participants, which includes people from the River, Buenaventura, Cali, and Bogotá, allowed the group to have a wide variety of perspectives on the relationship between bodies, memories and territories of the River. This has made it possible to investigate through arts the relationship with the River of people who were born in very different contexts and, at the same time, to investigate the definition of their identities, memories and connection with other territories they perceived as significant.

The creation process

The workshop was held for three days, in which they worked eight hours a day, in Cali, Colombia. The workshop’s agenda was designed by the facilitator and author of this article, using the techniques of the Theatre of the Witness and some preparatory exercises of Theatre of the Oppressed. During the weeks preceding the workshop, the facilitator and the Guía Nómada team discussed the following questions, which became the starting point of the creation process:

How can we co-create new identities together that are both rooted in the territory and history of the River and both capable of dialogue with other territories?

How can the ancestral memories of the River connect with a present marked by migration and violence of the armed conflict?

A few weeks before the start of the workshop, the facilitator proposed to the participants the “task” of bringing to the workshop:

A story of an ancestor of yours that inspires you with whom you feel connected. It can be a living or dead person, a person from your biological family or another person you chose as an ancestor (a neighbour, a friend, a school teacher when you were a child, a son, etc.). It cannot be an invented, literary or movie character, it must be a person who has really lived, who inspires you and with whom you feel connected.

An object that connects you with your life in the River and/or with the history of the River;

A song or music related to the River that makes you feel alive* and fills you with energy and strength.

On the morning of the first day, the facilitator proposed to the participants some games and exercises of knowledge, group creation and trust, based on games-exercises of Theatre of the Oppressed. The function of these exercises was to accompany the integration of the participants and the construction of a space of non-judgment, fun, creativity and deep listening. In the afternoon, the facilitator prepared a ritual space by placing a blanket on the floor, surrounded by candles and scents of “palo santo” (incense derived from the tree of Bursera Graveolens), and invited the participants to sit in a semicircle around the blanket. Then the facilitator invited each participant to stand up, one by one, stand in front of the semicircle and tell the story of the ancestor of her choice. After the group listened to all the stories, the facilitator invited the group to get up and work in pairs. In each pair, one participant acted as the director of the monologue and the other as an actress. The director helped her partner to stage the actress’s story in the form of a monologue; then the two participants switched roles.

On the second day, the facilitator asked each participant to present the object that connected them to the River, imagining that this object had memories and feelings and could speak in the first person. At the end of the second day, the participants also presented the songs and praise they had chosen. The detailed presentation and analysis of the eleven stories, objects and music goes beyond the objectives of this article, which is limited to presenting the creation process and its results and formulating some reflections on the themes that emerged during creation. However, we can highlight that the stories of the ancestors chosen by the participants mainly presented the lives of the female and male members of their family of origin (grandmothers, parents, siblings, etc.). In one case, the story focused on the grandmother of a participant who was a midwife and passed on to her daughter the traditional medical knowledge about medicinal plants. Another participant recounted the experience of a member of her family who survived a massacre perpetrated by an armed group in one of the riverside villages in 2001.

Staging of the massacre that occurred in the Yurumanguí River in 2001. Above the embroidery are visible the objects chosen by the participants: a paddle, a red raincoat and a rosary woven by a woman during the workshop, using a green branch. [Photo: Angelo Miramonti]

Staging of the massacre that occurred in the Yurumanguí River in 2001. Above the embroidery are visible the objects chosen by the participants: a paddle, a red raincoat and a rosary woven by a woman during the workshop, using a green branch. [Photo: Angelo Miramonti]

The objects chosen by the participants were:

A paddle (woman from the River)

A Guasa, musical instrument from the Colombian Pacific (woman from the River)

A hat made of interwoven vegetable fibres (woman from the River)

A rosary made of interwoven vegetable fibres (woman from the River)

A wooden plate (woman from the River)

A small tree trunk with knots (woman from the River)

The flag of the Black Communities Process (leader of Buenaventura)

A white embroidery (graphic design teacher from Cali)

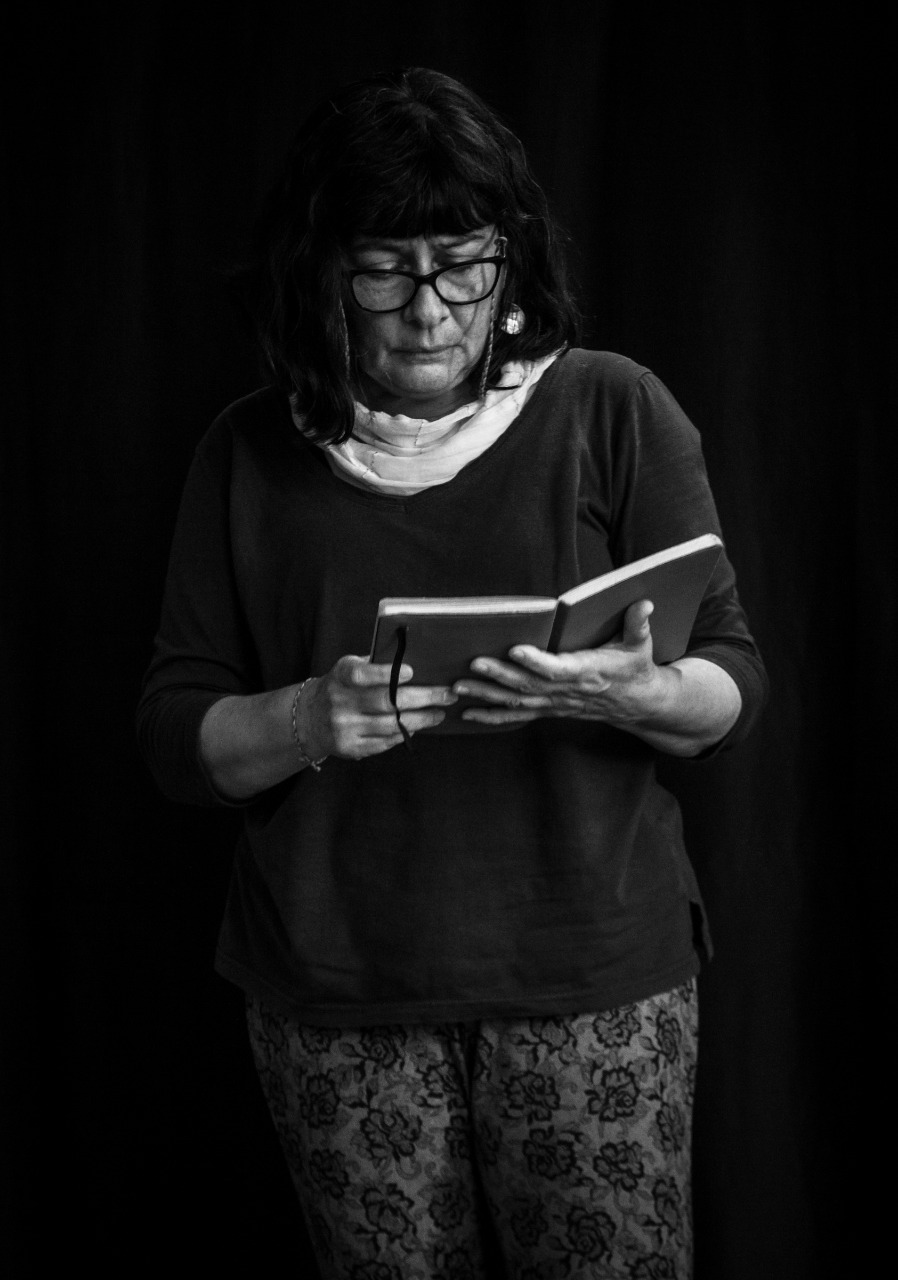

A field notebook (member of the National University team)

One chamber (member of the National University team)

A red raincoat (member of the National University team)

a notebook. [Photo: Angelo Miramonti]

[Photo: Angelo Miramonti]

presents her object: a wooden plate.

[Photo: Angelo Miramonti]

An in-depth analysis of the characteristics of every chosen object and of the memories that each object expressed goes beyond the scope of this article. However, we can highlight that the objects chosen by the six women of the River is concentrated on objects in wood and vegetable fibres that are locally self-constructed and used for practical purposes, such as eating (the plate), protecting themselves from the sun (the hat), cradling the new-born (the paddle) or for music and worship (the Guasa). The objects chosen by people outside the River are, on the contrary, related to their recent encounter with the River (the raincoat), with the need to record data in an unknown environment (the camera, the notebook), with the political militancy (the flag of the Black Communities Process) or with personal memories (the embroidery). We can also highlight that the chosen objects include ancient artefacts (the paddle) and technological devices (the camera), natural objects (the rosary woven with plant fibres) and political symbols (the Black Communities Process flag), reflective objects (the field notebook) and musical instruments (the Guasa).

On the third day, the participants worked in pairs and combined their ancestor stories with their “speaking objects” to create a monologue from these generative elements. The work was co-constructed with the participants and was not based on a text previously written by an author external to the group, the dramaturgy of the play came exclusively from the autobiographical accounts of the participants and the work of remembrance and imagination they did with the objects.

The play

The main result of the workshop was a play performed by the eleven participants, showing the interaction between ancestral memories and the constant reinvention of the Afro-descendant identity in the territory of the River. The intention of the participants was to present the play in the school of the villages along the River, to accompany the reflection of the youth on their cultural roots and their life projects, connecting the historical memory with the territory and the Afro-descendant identity with the social context of the River, marked by violent conflicts, loss of cultural identity and migration.

The play presents a series of eleven monologues about ancestors, interwoven with the monologues of the significant objects. Each participant appeared on stage, acted out the story of her ancestor, presented the monologue of her “speaking object”, left it on stage and left. The first object that entered the scene was the white embroidery, which the actress left on the floor before leaving the scene. This embroidery became the space where the other ten actresses and the actor who followed each other on stage left their objects. Each entrance and exit were marked by a song the participants chose and adapted in a way that the song “called” the object to appear on stage and present itself to the audience. At the end of the play, the round embroidery was on stage with ten objects on top. The ten actresses and the actor entered and sat around the embroidery, interlaced their arms, building a circle of bodies around the circle of objects, and began to sing a traditional song, metaphorically representing the connection between their bodies (the circle with interlaced arms), their memory (the song) and its territory (the objects). This final metaphor of the interconnection of bodies, music and objects is depicted in the photo below.

The celebration

After the presentation of the play, the participants sat in a circle around the embroidery and the objects, the facilitator lit a candle and invited the participants to take the candle one by one and share how they had felt during the workshop and what they considered to have been the main achievements of the process.

In relation to the first objective (offer a creative workshop where the participants could share their autobiographical stories and investigate, through art, the relationship between bodies, memories and territories), the participants highlighted that the autobiographical exercises had provided them with a space where they could share their personal stories and experiment, through acting and the animation of significant objects, their bodily relationship with their memories, and relate these memories to the territory through the connection with objects coming from their native land. All the participants highlighted in different ways that the workshop had been an experience of deep emotional connection among them and between them, their native land and the shared memories of the River. Reflecting from his facilitator’s point of view, the author considers that this was the objective that was most achieved, because most of the time of the workshop was dedicated to exploring the connections between the incorporated memories of the participants (both those coming from the River and those coming from outside) and their territories of origin.

Regarding the second objective (provide a space for healing and symbolic reparation to the inhabitants of the River, affected by the armed conflict), the participants felt that the wounds to heal most urgently were those related to the armed conflict at the present time: especially the ongoing forced recruitment of youth in their communities, the collective trauma their communities experienced in 2001 when an armed group perpetrated a massacre in one of their villages, and the ongoing infiltration of illegal groups in their land for illegal mining and drug trafficking. To this end, the participants highlighted that the workshop gave them a moment to share their experiences related to the armed conflict and that these moments of autobiographical storytelling were very rarely encountered during their daily lives in the River, where it was very difficult to leave their occupations and find moments of mutual listening and empathy. Moreover, the six participants from Yurumangui highlighted that being able to tell their stories and to be heard outside of their life context, in a space without judgment, to see their pain recognized by other women from the River and by other persons from other places was a moment to value their memories and reconcile with their painful experiences. In addition, the staging of the massacre that occurred in the River was an opportunity for one of the six women who experienced this event first-hand to be recognized not only as a victim, but also as a brave person, who managed to survive thanks to her abilities and now can assume the role of witness of this historical event before the Yurumangui communities, especially with the youth. Other participants emphasized that, although some of them had been more directly affected than others by the conflict, drug trafficking and forced recruitment of youth are affecting the entire population of the River. The six women concluded that the sharing of a story directly related to the conflict and the possibility of having a verbal and bodily dialogue on the subject had been a moment of inner healing for them. Reflecting on this second objective from the facilitator’s point of view, the author highlights that the workshop was unable to analyse in depth the violence in the present moment and specifically focus on the issues of drug trafficking and the forced recruitment, that constitute two of the major concerns of the participants from the River. We can then conclude that the second objective was only partially achieved, and that the issues related to the current situation in the River need another space and more time to be creatively investigated. The continuation of this work on the ongoing violence in the River remains as one of the paths for future workshops with the communities of the Colombian Pacific coast.

Regarding the third objective (creatively investigate how social transformations in the communities of the Pacific coast are expressed through music and song), the participants highlighted that the workshop allowed them to share their music and songs among themselves and with people outside the River, also modifying some texts and using them to weave together the ancestral stories and the animation of significant objects. However, the decision to concentrate on ancestral stories and objects (first and second objective) did not leave enough time to deepen the creative work with music. The work on the songs was limited to modifying the text of a song so that the choir outside the scene could evoke each object and ancestor’s monologue. The co-creation with local music was then an objective that only began to be pursued and that remains as an open path for future workshops.

In conclusion of the evaluation, the participants from Buenaventura, Cali and Bogotá highlighted that this experience had allowed them to revisit their relationship with the River (mainly mediated by the “Mingar la paz” project) and to understand more deeply many interior and social dynamics of its inhabitants. It is therefore important to highlight the fulfilment, at least partial, of two objectives that were not established from the beginning: to allow a deeper and more personal approach of the members of the project to the narratives of the women of the River and to allow the participants who did not come from the River to connect with their ancestral stories and to connect them with the stories of the six participants from the River. In conclusion, the evaluation highlighted that the workshop allowed each participant to connect, in a physical and artistic way, with their respective memories and their territories of origin and also to connect with each, strengthening their sense of belonging to a shared memory and collective identity.

Reflections on the co-creation experience

Reflecting on the experience, we can highlight that the workshop has shown the potential of testimonial theatre in accompanying a creative and transformative dialogue in communities affected by the physical, structural and symbolic violence of the armed conflict. In particular, we highlight the following three points.

1. The “speaking objects”: embodied memories and imagination

The animation of a “speaking object” allowed working on specific components of material life as identity markers. The objects were tied with the memories that the participants assumed as significant in their present, and allowed them to define their present identity through the object, connecting these material elements of their native land with their body during the performance. The “speaking objects” exercise was then at the same time an autobiographical/memory and a projection/imagination work, because, on the one hand, it allowed the participants to connect with their personal memories and, on the other, it stimulated them to imagine how these same memories would be communicated from a point of view external to their experience, as if the object had its own subjectivity and entered into dialogue with the audience as a different character. This “subjectivation” of an object - which gives life and discourse to a significant material element - allows the actress’s memories and emotions to be projected onto the object and expressed as if they were of a character, rooted in her personal history and, at the same time, a product of her imagination.

2. Memory and present

In the accounts of the participants, the political history of the Colombian pacific coast is interwoven with intimate and family memories of ancestral healers and the syncretic rituals of the Holy Week. The two mediations of the ancestral stories and of the objects are combined in a montage that connects the present with the ancestors of each actress, and each of them with all the others. The two concentric circles of bodies and objects that close the play visually represent the meeting of bodies, memory, territory and present, showing that this memory exercise does not create a “container” of past events, but is a present and constantly evolving act of recalling and relating past experiences that the subject feels as significant for their being in the world in the present. During the conclusion of the workshop, the actresses expressed the wish that, when the play was presented to an external audience, they could invite the spectators to continue the story, to continue weaving, in the form of oral stories, other memories and other objects coming from other territories. The dream that the group expressed was that the work would be constantly open to how the audience of each territory wanted to integrate it with their significant narratives. For this reason, the process presented in this article goes beyond a pure compilation of oral histories and aims to experiment with an artistic modality to establish new connections between actors, spectators and territories, in any context where the work is presented.

3. Present, hegemony and resistance

The workshop produced a play that is not a static portrait of the River’s culture, but a dynamic image, and presented its inhabitants as part of a process of co-creation of identities, in constant negotiation with the hegemonic western narratives and the threats posed by the armed conflict on their physician a cultural survival. Although the women did not explicitly address the issue of the hegemony of Western values in their communities, they highlighted that the lack of legal economic opportunities in the Yurumangui river caused the massive migration of young people to cities. In some stories, the women also mentioned the threat that large-scale mining and drug trafficking pose to the cultural survival of their communities. The physical violence of the armed groups and the structural violence represented by the lack of education and work opportunities were the main hegemonic relationships that appeared in the narratives of the participants. These elements of symbolic, physical and structural violence constitute another element of reflection to ensure that the policies of collective restitution designed by the Colombian government to community affected by the armed conflicts are proactively harmonized with local processes of cultural resistance in the communities.

It is also important to highlight that the field observations and the participants’ reflections show that the workshop was instrumental in producing changes at the interior, interpersonal and structural level. At the personal level, the workshop helped the participants heal some of the interior wounds related their violent past, including the assassination of some community members perpetrated by armed groups. At the interpersonal level, the workshop strengthened the links between the participants, (including also those from Buenaventura, Cali and Bogotá), motivating them to reinforce their collective strategies to cope with violence and cultural deprivation. At the structural level, the participants recognized the value of their individual narratives as part of a “broader story” of community resilience and the focus on their memories and territories as a strong motivation to address the structural historical and economic causes that lay underneath the conflict: the lack of legal economic opportunities for the youth, the disconnection of the community with the diaspora of its migrants living in Cali, Bogotá or abroad and the prejudices towards afro descendant people. The workshop accompanied the increase of the partecipants’ awareness of their power to change their lives together and to protect their rights. Although the definition of strategies to cope with structural violence remains beyond the objectives of this workshop, the evidence collected support the conclusion that Theatre of Witness could be an effective tool to foster community dialogue and collective healing. This theatre technique can also indirectly strengthen strategies of community resistance, empowering individuals and groups to engage in collective action for promoting peace in their territories.

Conclusion: co-creating interpretations

Reflecting on the whole process, we can highlight that this experience has allowed the six women of the River to see and recognize their own culture through the eyes of external people, and external people to know and value many aspects of their own culture as well as the Yurumanguí river’s culture. The constant dialogue between these two groups of people allowed each participant to recognize and value their own culture, while also reflecting on the other’s culture. This dialogue also made it possible to prevent the River’s culture from being perceived and presented as an object of analysis, defined by an external view. This dialogical approach also prevented the role of the women of the River from being just the “informants” in a traditional ethnographic investigation. The methods of offering a testimonial theatre workshop and the use of autobiographical storytelling, the animation of objects from daily life and the sharing of music from the River allowed to generate a process of co-creation of interpretations of the culture of the River, which arose from a crossing of gazes, represented by the meeting between the paddle, the music instrument, the hat in vegetal fibres, the rosary, the plate and the tree trunk on one side and the flag of the Black Communities Process, the embroidery, the field notebook , the camera and the raincoat on the other. The work also managed to present aspects of the River culture as parts of a rapidly changing system of beliefs and practices, mainly driven by the armed conflict, migrations and the modifications in the imaginations produced by the media. Thus, the play does not present the culture of the River as trapped in a fictional and non-historical “ethnographic present”. In addition, the constant articulation of this open work with other bodies, other territories and other memories that the actresses will find on their way, will allow deepening the awareness of their roots and the possibility of opening up to an encounter with the Western culture less marked by hegemonic relationships. It can be said that in this process each participant became a mirror for the other and allowed her to see and discover unknown aspects of herself. In conclusion, for the participants this experience was a co-creation of interpretations about themselves and about the other, a path that remains constantly open to new contributions from other bodies, other memories and other territories.

Bibliography

Boal A., Games for Actors and Non-Actors, Routledge, London 2002.

Bourdieu P. et alii, Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture, Sage Publications, Washington D. C. 2013.

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad, Biblioteca Nacional, Bogotá 2013.

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Una guerra sin edad. Informe nacional de reclutamiento y utilización de niños, niñas y adolescentes en el conflicto armado colombiano, Biblioteca Nacional, Bogotá 2017.

Creswell J. W., Shope R., Vicki L., Clark P., Green D.O., How Interpretive Qualitative Research Extends Mixed Methods Research, in “Research in the Schools”, vol. 13, n. 1, 2006, pp. 1-11.

Creswell J. W., Poth C. N., Qualitative Inquiry and research design, Choosing among Five Traditions, SAGE Publications, Washington D. C. 1997.

Fritz B., The Courage to Become – Augusto Boal’s Revolutionary Politics of the Body, Danzig & Unfried, Vienna 2021.

Gailliard B. M., Communication and Identity Negotiation Processes by Professionals in Health Care Organizations – Examining Race, Gender, and Class Intersections, University of California, Santa Barbara 2013.

Grant D., Jennings M., Processing the Peace: An Interview with Teya Sepinuck, in “Contemporary Theatre Review”, vol. 3 n. 23, 2013, pp. 314-322.

Grant D., Shoulder to Shoulder: The Co-Existence of Truths in the Theatre of Witness, in Aa. Vv., Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces, edited by H. Epinoux & F. Heavy, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge 2016.

Gretchen A., Colombian Peace Communities: The Role of NGOs in Supporting Resistance to Violence and Oppression, in “Development in Practice”, vol. 16, no. 3-4, 2006, pp. 278-291.

Grierson E., Brearley L., Creative Art Research: Narratives of Methodologies and Practices, RMIT, Melbourne 2009.

Kadende R. M., Language, Cultural Discourse, and Identity Negotiation Internet Communication Among Burundians in the Diaspora, Indiana University, Bloomington 1998.

Kimberly D. F., al Sayah F., Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature, in “Arts & Health”, vol. 3, no. 2, 2011.

Lawler P., Peace Studies, in Aa. Vv., Security Studies: An Introduction, edited by P. D. Williams & M. McDonald, Routledge, London 2008.

Lynn K., Sides S., Collective Dramaturgy: a Co-consideration of the Dramaturgical Role in Collaborative Creation, in “Theatre Topics”, vol. 13, no. 1, 2003, pp. 111-115.

McIntyre A., Participatory Action Research, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks 2008.

Miramonti A., How to Use Forum Theatre for Community Dialogue – A Facilitator’s Handbook, Lulu Press, Morrisville-NC 2017.

Miramonti A., Healing and Transformation Through Arts: Theatre for Reconciliation in “Educazione Aperta”, n. 6, pp. 40-60.

Miramonti A., Stories of Wounds, Paths of Healing: Theatre of Witness with Victims of the Colombian Conflict, in “Educazione Aperta”, n. 8, 2020, pp. 65-88.

Piaget J., The language and thought of the child, vol. 5, Psychology Press, Milton Park 1959.

Rogoff B., Apprenticeships in thinking, Oxford University Press, New York 1990.

Sepinuck T., Living with Life. The Theatre of Witness as A Model of Healing and Redemption, in Aa. Vv., Performing New Lives: Prison Theatre, edited by J. Shailor, Kingsley, London 2011.

Sepinuck T., Theatre of Witness – Finding the Medicine in Stories of Suffering, Transformation and Peace, Kingsley, London 2013.

Schugurensky D., On informal learning, informal teaching, and informal education: Addressing conceptual, methodological, institutional, and pedagogical issues, in Aa. Vv., Measuring and Analyzing Informal Learning in the Digital Age, edited by O. Mejiuni, P. Cranton. O. Táíwò, Arizona State University Press, Tucson 2015.

Smith H., Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2009.

Steele, A. Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War, Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2018.

Stelter R., Experience-Based, Body-Anchored Qualitative Research Interviewing, in “Qualitative Health Research”, vol. 20, no. 6, 2010, pp. 859-867.

Unidad para las Víctimas, Registro Único de Víctimas, Bogotá 2016.

Vygotsky L. S., Thought and language, MIT Press, Cambridge-MA 1962.

Vygotsky L. S., Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, Harvard University Press, Cambridge-MA 1978.

Vygotsky L. S., Thinking and speech, in L. S. Vygotsky, The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky, Volume 1: Problems of general psychology, edited by W. Rieber & A. S. Carton, Plenum Press, New York 1987.

Vivas C., Dramaturgia y presente, Umbral Teatro, Bogotá 2012.

The author

Angelo Miramonti (Ph.D.) is professor of Community Theatre at the Institute of Fine Arts in Cali (Colombia) and Lecturer of Testimonial Theatre at the University of Applied Arts in Würzburg (Germany). He is a registered Drama therapist in Italy and the founder of the “Arts for Reconciliation” research project in Cali (Colombia) focusing on the use of arts to accompany dialogue and reconciliation among former combatants and victims of the Colombian armed conflict. He authored a number of articles on Theatre and Arts for Reconciliation and the manual How to Use Forum Theatre for Community Dialogue – A Facilitator’s Handbook (translated in Spanish, Italian, French and Arabic). He trained in Theatre of the Oppressed, Theatre of Witness, Drama Therapy and Ritual Theatre and facilitates in English, French, Spanish Portuguese and Italian. He also coordinated rehabilitation programs for child soldiers in Uganda, Congo and West Africa and carried out anthropological and mental health research on healing and possession cults in Senegal. His book: Amina. Portait d’une femme habitée par les esprits ancestraux is an account of this ongoing research.

A. Steele, Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War, Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2018, p. 22.

https://www.unhcr.org/colombia.html [retrieved on the 11th of June 2021].

Unidad para las Victimas, Registro Único de Víctimas, Bogotá 2016.

The root causes of violence in the Colombian Pacific coast are presented in: Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, Colombia: memorias de guerra y dignidad, Biblioteca Nacional, Bogotá 2013.

For an overview of community resistance strategies and the role of international NGOs in supporting them, see A. Gretchen, Colombian Peace Communities: The Role of NGOs in Supporting Resistance to Violence and Oppression, in “Development in Practice”, vol. 16, no. 3-4, 2006, pp. 278-291.

This case study also aims at documenting a psychosocial intervention that proved effective and could be implemented at a larger scale, supporting the Colombian Government reparation policies, within the framework of the “Law of Victims and Land Restitution” (Law 1448, 2012).

A. Miramonti, Healing and Transformation Through Arts: Theatre for Reconciliation, in” Educazione Aperta”, n. 6, 2019, pp. 40-60.

T. Sepinuck, Theatre of Witness – Finding the Medicine in Stories of Suffering, Transformation and Peace, Kingsley, London 2013.

Sepinuck highlights this aspect of Theatre of Witness in D. Grant, Shoulder to Shoulder: The Co-Existence of Truths in the Theatre of Witness, in Aa. Vv., Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces, edited by H. Epinoux & F. Heavy, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge 2016.

A detailed account of the dramaturgy of these plays based on testimonies of relatives of victims of the Colombian conflict is presented in Vivas C., Dramaturgia y presente, Umbral Teatro, Bogotá 2012.

For a Theatre of Witness experience with victims of the Colombian armed conflict see Miramonti A., Stories of Wounds, Paths of Healing: Theatre of Witness with Victims of the Colombian Conflict, in “Educazione Aperta”, n. 8, 2020, pp. 65-88.

R. Stelter, Experience-Based, Body-Anchored Qualitative Research Interviewing, in “Qualitative Health Research”, Vol. 20, Issue 6, 2010, pp. 859-867.

D. F. Kimberly, D. F., al Sayah, F., Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature, in “Arts & Health”, vol. 3, n. 2, 2011.

K. Lynn, S. Sides, Collective Dramaturgy: a Co-consideration of the Dramaturgical Role in Collaborative Creation, in “Theatre Topics”, vol. 13 n. 1, 2003, pp. 111-115 and B. Fritz, The Courage to Become - Augusto Boal’s Revolutionary Politics of the Body, Danzig & unfried, Vienna 2001.

J. W. Creswell, R. Shope, L. Vicki, P. Clark, D. O. Green, How Interpretive Qualitative Research Extends Mixed Methods Research, in “Research in the Schools”, vol. 13, no. 1, 2006, pp. 1-11.

A. McIntyre, Participatory Action Research, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks 2008.

J.W. Creswell, C. N. Poth, Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, choosing among five traditions, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks 1997.

Before the workshop, the Mingar la paz Project asked all the above participants to give their informed consent to be photographed and filmed for the purposes of the Mingar la Paz project, including having their photos displayed in this article and videos that were produced and eventually published during an exhibit organized in Bogotá in February 2020.

T. Sepinuck, Theatre of Witness – Finding the Medicine in Stories of Suffering, Transformation and Peace, Kingsley, London 2013.

Theatre of the Oppressed is a drama method systematized by the Brazilian director Augusto Boal from the 1960ies to 2009. During the workshop, the author facilitated some of the “games-exercises” systematised by Boal. For a detailed description of these theatrical exorcises, see A. Boal, Games for Actors and Non-Actors, Routledge, London 2002 and A. Miramonti, How to Use Forum Theatre for Community Dialogue – A Facilitator’s Handbook, Lulu Press, Morrisville NC, 2017.

To date, the play was never performed in the schools of the River, also due to the pandemic’s restrictions, but it remains as a follow up activity of the Project for 2021 and beyond.

For the purposes of this paper, we adopt Bourdieu’s definition of symbolic violence emaborated in P. Bourdieu et alii, Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture, Sage, Washington D. C. 2013.

For a theoretical definitions of identity negotiation see R. M. Kadende, Language, Cultural Discourse, and Identity Negotiation. Internet Communication Among Burundians in the Diaspora, Indiana University, Bloomington 1998 and B. M. Gailliard, Communication and Identity Negotiation Processes by Professionals in Health Care Organizations – Examining Race, Gender, and Class Intersections, University of California, Santa Barbara 2013.

For the purposes of our research we adopt the concept of “co-creation” as a distinctive approach to pedagogy and art creation, where the emphasis is put on collaborative or partnership working. This concept was initially defined by Piaget in J. Piaget, The language and thought of the child, vol. 5, Psychology Press, Milton Park 1959 and by L. S. Vygotsky, Thought and language, MIT Press, Cambridge-MA 1962. Some decades later, the concept of co-creation was also discussed by B. Rogoff, Apprenticeships in thinking